Active Myth Busted

“...after all costs are considered (spreads, market impact, management fees, taxes, etc.), the net return of all transactions must underperform the market benchmark. This is one of the few mathematical certainties in investing.”

MythBusters is one of those cable shows that I find myself gravitating toward whenever I’m channel surfing. It’s just one of those shows that I find wildly entertaining. I know, I know . . . nerd alert! But that’s what you get when you ask an investment guy to “show a bit of personality.” In any event, for those who are less familiar, each episode follows a similar structure: A common myth is presented and then the hosts apply scientific method and experiments to test its validity. Watching an episode recently got me thinking about certain investing myths that never seem to die. In particular, there are a number of myths surrounding indexing that could really benefit from the debunking process. So I decided to dedicate a series of blogs to tackling these indexing myths and hopefully set the record straight.

Probably the most common myth I hear, and I hear it a lot, is, “We’re happy to index large-cap U.S. stocks, but we prefer active in small-cap or international markets.” Makes sense, right? After all, large-cap stocks, those in the S&P 500 Index, for example, are closely followed by analysts, traders, portfolio managers, and sell-side research firms. All that coverage should make large-cap U.S. stocks highly efficient and, therefore, difficult to beat. On the other hand, such coverage is much less likely for a small-cap emerging markets firm. Analysts who are able to “discover” that particular stock have the potential to add a winner to their actively managed portfolios. As a result, we have the industrywide proclivity to invest in active managers in these so-called inefficient market segments. Of course, Vanguard does believe in the potential for low-cost, talented active management to add value—that’s not the issue at hand—it’s the view that one should consider active in certain markets because they are thought to be inefficient.

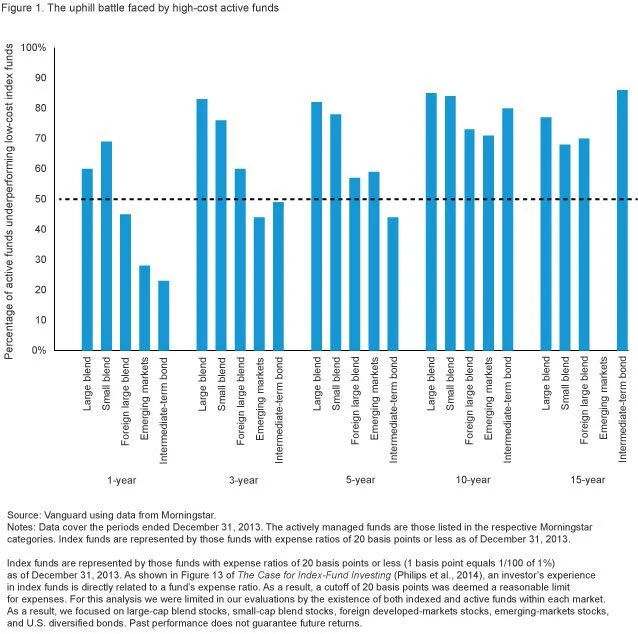

While we can perform many different tests, really the only one we need also happens to be the easiest—the sophisticated exercise also known as the eyeball test! If these markets were less efficient, we’d see a large portion—dare I say majority—of active funds outperforming not just their own benchmark, but also low-cost passive alternatives. However, in recently updated research on indexing, Vanguard found that once ”dead funds” (i.e., funds that were merged or liquidated) were included, 84% of actively managed small-cap U.S. funds, 73% of non-U.S. developed markets fund and 71% of emerging markets funds underperformed the average return of low-cost index funds in those same categories over the ten years ended 2013 (see figure 1. below). By my count, that’s three out of every four funds that failed to deliver on the theory that these markets are less efficient and therefore ripe for outperformance. Compare that to large-cap U.S. stocks, where 85% of funds underperformed.

For those who argue that the past ten years were unkind to active and atypical of the normal experience, the results did not appear overwhelmingly in favor of stock picking even during the last three years. Seventy-six percent of small-cap funds, 60% of non-U.S. developed markets funds, and 44% of emerging markets funds underperformed the average return of low-cost index funds. While somewhat better than the 10-year numbers, these aren’t results that engender confidence in the ability to systematically capture supposed market inefficiencies! Even under the best of circumstances, emerging markets funds were essentially a coin-flip probability of outperforming a low-cost passive option.

So what’s going on here? The concept of the zero-sum game (all dollars invested collectively equal the market and for every overweight there must be an offsetting underweight) doesn’t need market efficiency to hold true. The zero-sum game holds true in every market. And in every market there always needs to be a buyer and seller. This also means that someone will be a winner and someone will be a loser—both positions cannot be winners. And after all costs are considered (spreads, market impact, management fees, taxes, etc.), the net return of all transactions must underperform the market benchmark. This is one of the few mathematical certainties in investing. The beauty of indexing is that the strategy is an attempt to replicate the returns of a market index at low cost. In this way, index investors allow the zero-sum game to work in their favor. And this means that low-cost passive investors also benefit from the negative-sum game of the higher costs of active management.

Myth, busted.

Want a preview of our insights on other common myths, criticisms, and misconceptions associated with indexing? You’ll find them in our recent research note.

Read Vanguard White Paper (pdf)

Notes:

Mutual funds and investing are subject to risk, including the possible loss of the money you invest.

Prices of mid- and small-cap stocks often fluctuate more than those of large-company stocks.

Investments in stocks or bonds issued by non-U.S. companies are subject to risks including country/regional risk and currency risk. Funds that concentrate on a relatively narrow sector face the risk of higher share-price volatility. It is possible that tax-managed funds will not meet their objective of being tax-efficient. Because company stock funds concentrate on a single stock they are considered riskier than diversified stock funds.

© 2014 The Vanguard Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Used with permission.