Be Average

No one wants to be average. Just think about the fictional Lake Wobegone, where “all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average.” The mathematics of whether more than 50% of anything can be above average aside (impossible), this quote has relevance in the investing derby. Everyone wants (deserves?) to be above average! Who in their right mind would settle for being average? Not I. And I imagine the vast majority of the readers don’t want to be average either. After all, we don’t celebrate average athletes, musicians, or celebrities. We certainly don’t celebrate average investors. Would George Soros, Peter Lynch, or Warren Buffett be household names if they weren’t in the far right tail of the distribution of skill?

In my opinion, the biggest challenge we all face as investors and fiduciaries is the human brain. Specifically, the emotions, influences and hidden assumptions that perpetually reside in our collective minds. An example: Perusing past clips of various finance shows on popular cable TV channels, I came across an apropos summary on CNBC: While many experts still advise only investing in index funds, today’s market shows how a little homework can allow investors to do so much better. Wow! Just a little bit of effort can lead to a result far better than average? Sign me up.

But this is where our emotions and hidden desires are our own worst enemy. Often our desires fly in the face of mathematical truth and empirical evidence. The desire for greatness is a powerful incentive. In fact, you’d be surprised at how often advisors tell me, “I need active managers for the alpha. Indexing won’t help close my clients’ savings gap.”

But the zero-sum game doesn’t care if you need alpha to close a savings gap. The zero-sum game says that all investors collectively must equal the market, and after the costs of execution, trail the market. It’s basic math. But that basic math is the single greatest hurdle we all face. Odds are, the entity on the other side of your trade won’t be me—it’ll be another highly skilled active manager with opposing viewpoints. So if you need alpha, then you’ll need to take it at the expense of someone else. Alpha isn’t just lying around waiting to be scooped up.

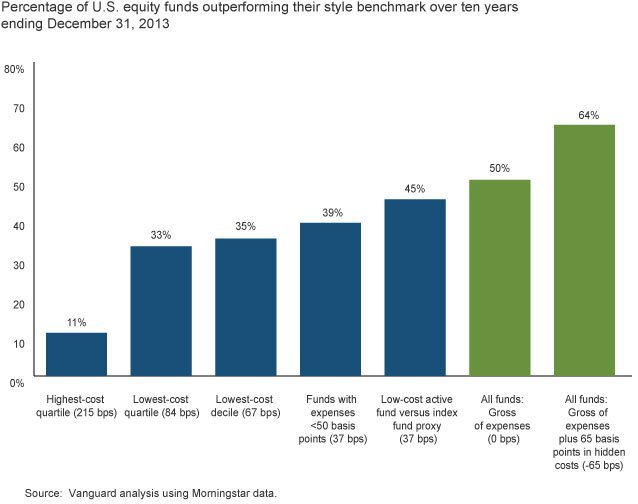

So where does this leave us? The challenge we all face is that skill is difficult to find—and even more difficult to capture consistently over time. Lowering the cost of active is an important step in improving the odds of capturing alpha. For example, looking at the U.S. equity mutual fund universe in Morningstar, only 11% of the funds in the highest-cost quartile managed to outperform a style benchmark for the 10 years ended 2013. In contrast, 33% of the funds in the lowest-cost quartile outperformed. Further stratifying the lowest-cost quartile to look only at funds with expenses less than 50 bps, we find that 39% of these funds managed to outperform.

If we compare the cohort of funds with expenses less than 50 bps to the same indexes adjusted for the expenses of a low-cost index fund (I assumed 20bps annual expense ratio), the percentage that outperforms rises to 45%.¹ Clearly then, index funds, in their attempt to deliver the average returns of all investors in a particular market, can deliver above-average performance. And while one could reasonably expect 100% of well-managed index funds to underperform their benchmarks, they should do so with minimal deviations.

Does that mean that skill doesn’t exist? No. But as John Bogle notes in “The Arithmetic of ‘All-In’ Investment Expenses,” the execution costs of managing an active portfolio can result in a sizeable headwind. He conservatively estimates an additional 65 bps of expenses on top of the reported expense ratio resulting from transaction costs and cash drag alone. This is potentially a key reason why, even when using gross returns, the success of active has been a literal coin-flip at 50% over the last 10 years. If however, we look at theoretical gross returns by adding back in that 65 bps drag, we see outperformance start to show up for a majority of funds. So skill exists, it just hasn’t been able to overcome the high costs of execution.²

The key takeaway is that unless you can reduce all costs of active, efficiently capturing the average returns of a market have been far from “just average” when compared with investors’ collective experiences. Perhaps indexing CAN be the closest representation we have of Lake Wobegone, where many investors DO have the ability to be above average simply by being passive.

_________________________________________

1 - We cannot compare the active fund cohort to passively managed funds because passively managed funds with 10 years of history do not exist for all categories.

2 - Note that we are showing surviving funds only. Including funds that closed or merged over this period would change the results, as documented in Vanguard research papers “The case for index-fund investing” and “The mutual fund graveyard: An analysis of dead funds.”

Note: Investing is subject to risk, including the possible loss of the money you invest.

© 2015 The Vanguard Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Used with permission.